By Olga Orozco

Translated by Mary Crow

The Stranger

He passed among you,

people kindly as the fire's warmth in a neighboring hut.

But what was your accent except a jagged dagger quivering

in the depth of his breast? He watched you pass,

days drowsy as beasts in humble pastures.

But what was your peace except sand burning under his eyelids?

Far away the wind blew leaving no cheeks salty.

Far away a place exists for his shade beside the fresh shades

of his ancestors.

Far away he will be the absent one less absent now.

Oh, dry your tears

that do not quench the thirst of the stranger.

Keep your prayers:

he didn't ask for love or any other heavenly exile.

And let earth lift up its lullabies like an insulted stepmother:

"I bear a heart as harsh and angry as the leaf of the fig tree."

FAR AWAY, FROM MY HILL

Sometimes it was only a call of sand on the windows,

grass in the still meadow suddenly trembling,

a transparent body that softly passed through the walls

leaving an icy glow in my eyes,

or sometimes only the sound of a stone rolling

over midnight’s

unspeakable darkness;

sometimes, only the wind.

I recognized in these things distant messengers

from a land submerged with the world

under my forehead’s high shadows.

Perhaps I had loved them under another sky,

but solitude, ruins, and silence remained always the same.

Later, in the growing night,

I looked from above at the bent head of a woman dressed in

sorrow

who walked through all her ages as if through a garden

formerly loved.

At path’s end, before the sleeping plains began,

a memorable shimmer, barely a pale and cruel color,

hid her goodbye;

and, beyond, she recognized nothing.

Who were you, woman lost among foliage like earlier

springtimes,

like someone who returns from time to repeat her cries,

desires, slow gestures with which yesterday she half-opened

her days?

My soul, only you.

You appeared in my life as if in a distant music,

forever enveloping,

suspended from who knows what wall of tender homelessness,

listening to the leaves’ stifled murmur over my sleepy

youth,

and you chose the sad, the hushed, all that is born beneath

oblivion.

In what corner of yourself,

in what deserted corridor do the clamorous steps of a happy

season

resound,

murmur of water in some meadow prolonging the sky,

hopeful song with which dawn ran to meet us,

and also words, no doubt as distant from the special place,

and in which the impossible was dying?

You don’t respond at all, because any answer from you

has already been

given.

Perhaps you’ve lived everything, that burned,

leaves only dust of undying sadness,

or greets in you, through memory,

an eternal home simultaneously welcoming and abandoning us.

You don’t ask anything, ever, because there’s no one to

answer you now.

But, over the hills,

your sister, memory, a young branch still in her hands,

tells once more the unfinished story of a misty country.

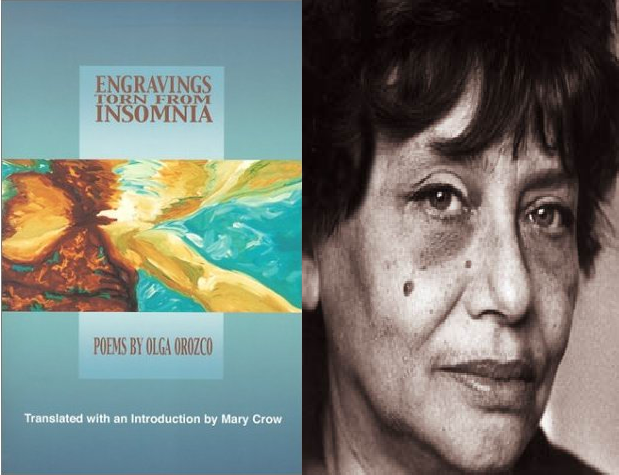

Olga Orozco (1920-1999) (real name Olga Noemí Gugliotta) was

an Argentine poet born in Toay, La Pampa. She spent her childhood in Bahía

Blanca until she was 16 years old and she moved to Buenos Aires with her

parents where she initiated her career as a writer.

Orozco directed some literary publications using some

pseudonymous names while she worked as a journalist. She was a member of

so-called «Tercera Vanguardia» generation, which had a strong surrealist

tendency . Her poetic works were influenced by Rimbaud, Nerval, Baudelaire,

Miłosz and Rilke. She died in 1999 in Buenos Aires at the age of 79.

OIga Orozco’s poetic voice is as recognizable and unique as

a fingerprint. No other poet anywhere in the world has a voice which sounds

like hers. In a language that is a torrent of words, passionate and yearning,

stumbling and pleading, Orozco’s poems pour out an image-laden vision. Her

poems seem to be called forth by shaman powers, out of a magical realm where

primitive ritual, fairy tale, chaos, and nightmare mingle. Elements of the

modern world float with fragments of dreams and tags of childhood

recollections, making readers feel both dizzy and at home. Hers is a search for

meaning and identity. Written in free verse, Orozco’s poetry maintains as Jil Kuhnheim

has said “a quality of ceremonial

orality, making it a kind of ritualization of speech”.

Olga Orozco was one of the most obsessive of contemporary

poets, returning again and again to certain themes, images, and words, and

mulling over the significance of her experience as if she were a cabbalist

reading the book of life and giving us her interpretations. Embedded in these

interpretations we discover many events from Orozco’s life even though her

poems appear focused on a cosmic rather than a human realm. Simply put, Orozco

was a thoroughly human poet in her suffering and in her passionate complaints

and celebrations. As Venezuelan poet Juan Liscano has noted, “She’s standing at

the limit where night and day are confused, when it’s dawn or dusk that’s

growing blue, as if an apparition from the beyond were drawing near, or a

character from close by were stealing away.”

But where she is “standing” in her poems is less a physical

place than an interior space with the abyss around it, a place that is only one

of the reoccurring “realities” in Orozco’s poems. Another reality is the

speaker’s alternation between self as subject and object, or the dual selves in

the poems, often wrestling with each other as she speaks through the “I” of the

poem and also to a “you” who is beside or inside the “I.” At times this

struggle is located in the body, which is presented in Orozco’s poetry as

fragmented, inadequate, and with a will of its own which the “I” has difficulty

directing. At other times the struggle seems to move out into the invisible

world.

Or, again, Orozco locates the struggle in language which

slips and slides in its torrent of several levels of meaning; it is a language

that is veiled, embodying secrets and labyrinths. Thus, the intelligence speaking

in a poem is confronted by many kinds of difficulties as she addresses her own

internal split, the unknowable nature of the world she occupies, her sense of

the fragmentation of her body, and her struggle to create meaning with words

that may be decorations or signals or signs. Nonetheless, the poems, embedded

in a dense imagery based in the phenomena of the physical world but giving rise

to the visionary, represent the courage of the speaker’s ongoing struggle and

her plunge into that abyss where the struggle takes place and where poems

arise.

The above poems are representative of her interior landscape.

No comments:

Post a Comment