NOVEMBER 3RD

By Miyazawa Kenji

Translated by M A K O T O U E D A

neither yielding to rain

nor yielding to wind

yielding neither to

snow nor to summer heat

with a stout body

like that

without greed

never getting angry

always smiling quietly

eating one and a half pints of brown rice

and bean paste and a bit of

vegetables a day

in everything

not taking oneself

into account

looking listening understanding well

and not forgetting

living in the shadow of pine trees in a Weld

in a small

hut thatched with miscanthus

if in the east there’s a

sick child

going and nursing

him

if in the west there’s a tired mother

going and carrying

for her

bundles of rice

if in the south

there’s someone

dying

going

and saying

you don’t have to be

afraid

if in the north

there’s a quarrel

or a lawsuit

saying it’s not worth it

stop it

in a drought

shedding tears

in a cold summer

pacing back and forth lost

called

a good-for-nothing

by everyone

neither praised

nor thought a pain

someone

like that

is what I want

to be

(1931)

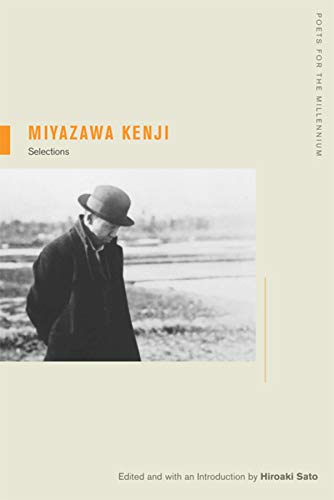

The Japanese poet Miyazawa Kenji, who died in 1933 at the age of thirty-seven, became a culture hero on the strength of a single brief poem written toward the end of his obscure and voluntarily impoverished life. “November 3rd”—an unpublished notebook entry probably intended more as a prayer than a poem—sketches a portrait of an idealized ascetic.

“November 3rd” remains universally familiar in a way that no poem has in the West since Rudyard Kipling’s “If ” or Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees.” The world it evokes, a world of thatched huts and drought-stricken Welds, sickly children and rice farmers with bent backs, might appear anachronistic when set against the Japan of computer graphics and advanced robot technology—unless you were to take a bus into the mountains and see landscapes and faces lifted intact from a Miyazawa poem.

In his own way Miyazawa came quite close to realizing the saintly ideal set forth in “November 3rd.” The son of a pawnbroker in northern Japan’s Iwate Prefecture (a backward region affected with chronic crop failures), he converted in adolescence to the Nichiren sect of Buddhism. Taking as his guide the Lotus Sutra, which teaches the availability of Buddhahood to all sentient beings, he dedicated himself to the welfare of the local farmers, becoming a sort of one man cultural and agricultural missionary, teaching crop rotation and soil improvement and exploring methods of food and drought prevention. In the meantime, he strictly observed vegetarianism, often subsisting on a poorer diet even than the local people were used to, and as a result he ruined his health and ultimately died of Pneumonia.