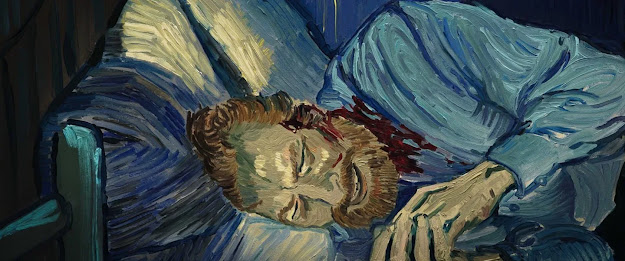

Suicide Room

By Wislawa Szymborska

Translated by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak.

I'll bet you think the room was empty.

Wrong. There were three chairs with sturdy backs.

A lamp, good for fighting the dark.

A desk, and on the desk a wallet, some newspapers.

A carefree Buddha and a worried Christ.

Seven lucky elephants, a notebook in a drawer.

You think our addresses weren't in it?

No books, no pictures, no records, you guess?

Wrong. A comforting trumpet poised in black hands.

Saskia and her cordial little flower.

Joy the spark of gods.

Odysseus stretched on the shelf in life-giving sleep

after the labors of Book Five.

The moralists with the golden syllables of their names

inscribed on finely tanned spines.

Next to them, the politicians braced their backs.

No way out? But what about the door?

No prospects? The window had other views.

His glasses lay on the windowsill.

And one fly buzzed---that is, was still alive.

You think at least the note could tell us something.

But what if I say there was no note---

and he had so many friends, but all of us fit neatly

inside the empty envelope propped up against a cup.

Wislawa Syzmborska, 1996 Nobel Laureate, was one of the great masters of Modern Polish poetry. Wislawa approach the topic of suicide in a quieter language. In this poem, the speaker makes an inventory of items that he sees upon visiting the apartment of possibly a friend who committed suicide.She seems to be seeking the reasons his choice to kill himself. She initially examines the victim’s circumstances ( I'll bet you think the room was empty./Wrong. There were three chairs with sturdy backs./A lamp, good for fighting the dark.).

The striking feature of this poem is that it contains no statistics, no quotes from experts, no discussion of antidepressants, none of the sound-bite analysis. It methodically progresses with unremitting detachment in the interrogation. In its analytical inventory, it offers little of conventional sympathy or pathos we might expect from the situation. It is rather forensic and deals more with facts than feelings. Considering the man’s desperation, she writes:

No way out? But what about the door?

No prospects? The window had other views.

The poem goes on to describe the room of the dead man, a place filled with photos, records, books, "a carefree Buddha and a worried Christ," a notebook that held the addresses of his friends. A richly furnished room. Szymborska’s irony is prevalent, allowing her to portray the scene with penetrating coldness.

Ultimately, the speaker wishes to force us to look harder

and more closely, more skeptically at the facts, and the evidence suggests the

suicide was mismatched n the things of the world around him. It is interesting to observe

how conventional and automatic our own default instincts for psychological

reading are. Our tendency is to read through the surface of the poem for traces

of the speaker’s “actual” feelings of bitterness or grief. Yet that wounded

surface is not there for us to shed tears. I like that poetic coldness and

absence of melodrama and withdrawal of empathy. Yet the last lines hit us hard

and make us wonder about humans around him.

Even though he had so many friends to rely on, he finally found them inadequate to help him. Sometimes, just because there are friends out there there doesn't mean we can talk to them. And just because we can talk to them doesn't mean that they'll understand.

The empty envelope enveloping his friends shows the vacuity of everything when confronted by utter desperation, defeat and surrender.

No comments:

Post a Comment