Scorched Maps

by Tomasz Rozycki

Translated by Mira Rosenthal

For J. B

I took a trip to Ukraine. It was June.

I waded in the fields, all full of dust

and pollen in the air. I searched, but those

I loved had disappeared below the ground,

I waded in the fields, all full of dust

and pollen in the air. I searched, but those

I loved had disappeared below the ground,

deeper than decades of ants. I asked

about them everywhere, but grass and leaves

have been growing, bees swarming. So I lay down,

face to the ground, and said this incantation—

about them everywhere, but grass and leaves

have been growing, bees swarming. So I lay down,

face to the ground, and said this incantation—

you can come out, it’s over. And the ground,

and moles and earthworms in it, shifted, shook,

kingdoms of ants came crawling, bees began

to fly from everywhere. I said come out,

and moles and earthworms in it, shifted, shook,

kingdoms of ants came crawling, bees began

to fly from everywhere. I said come out,

I spoke directly to the ground and felt

the field grow vast and wild around my head.

the field grow vast and wild around my head.

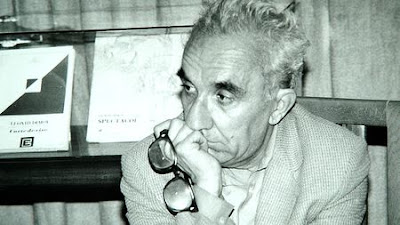

Tomasz Rozycki is one of the finest Polish poets living today.This poem originates from a trip he undertook to Ukraine when he visits an area where his forefathers lived before the Second world war. The poet's ninety-year-old grandmother—when she found out he was going there for the first time so many years after the nightmare of the war—wanted him to tell her if there was any sign of her house left, even though she didn’t have much illusion that there would be.

Many families were resettled from that area after the Second World War because of the agreement between Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt, who won the war. At that time the borders of Poland were shifted west, and the Poles who lived in the area that was lost to the Soviet Union were transported by freight train west to Pomerania and Silesia, where I live today. These changes affected several million people, who had to abandon their homes, neighbors, traditions, memories, and God knows what else—everything that had happened on that ground for centuries.

The Second World War in particular afflicted those living in this area, Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Armenians—everyone who had helped form the unusual mosaic of cultures and languages there over the centuries. They experienced the terror of Soviet occupation—mass executions and the transportation of millions of victims to the Gulag and forced labor camps deep within Russia—which met with the terror of the Nazis as the Germans, in a systematic way during the extermination of the area’s population, prepared their future “living space.” Inconceivably, at the same time a brutal domestic war continued between Ukrainian nationals, who cooperated with Hitler during the period, and the Polish resistance—a war in which neighbors murdered neighbors and the number of victims and the atrocity of what happened calls to mind ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia. The poet's family was one of those that experienced all of the terror and mourned each of the victims.

The mournful silence of the place that he arrives in search of his roots, overwhelms the poet. He lies on the ground and makes this poignant incantatory plea to all his forefathers buried there to come out as the terror regimes are over and they can now live safely.

From "Colonies" Tomasz Rozycki . Translated by Mira Rosenthal. The introduction about this poem is from the poet's preface to it published by PEN America.